WE'VE BEEN HERE BEFORE

The Fed finds itself in the uncomfortable spot of having Kevin Warsh being right twice

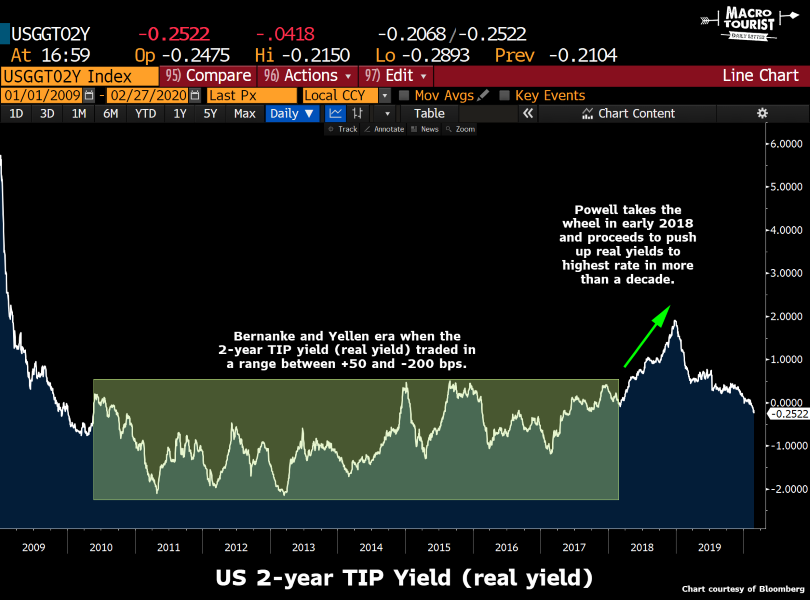

I want to take you back to 2018. At the time, Powell was just a few months into the job, and "gosh darn it!", he was going to show the market who was boss. So he was hawkish. More hawkish than the market had seen in over a decade.

Don't believe me? Have a look at the 2-year TIP yield.

At first his hawkishness felt great. Trump had just cut taxes, so the American economy was humming along nicely. After all, the rest of the world was busy constraining fiscal policy and here was America doing the exact opposite. Capital poured into the U.S. The stock market rose, along with the US Dollar. Nothing could go wrong.

Except it did. Powell was starving the world of US dollars. Global credit started to contract, and before you knew it - the global economy was showing some severe strains.

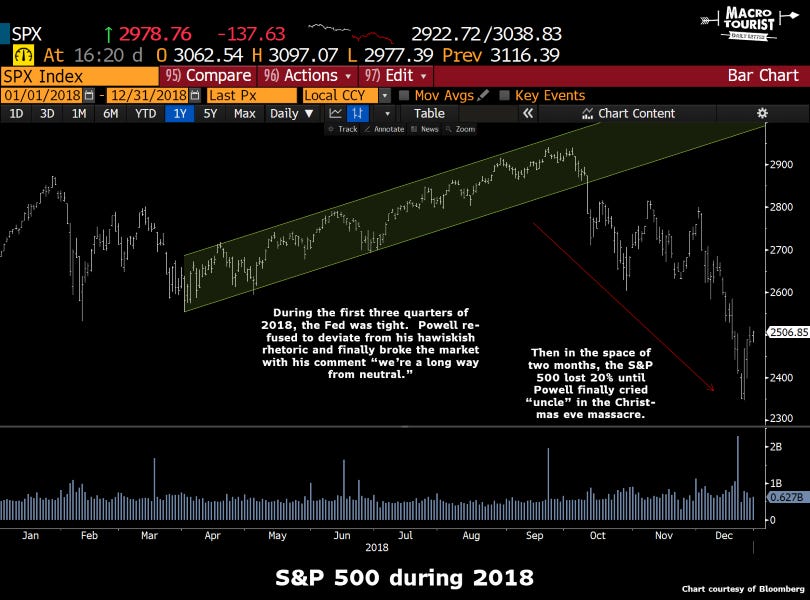

It finally came to a head in late September when Powell uttered those infamous words; "we're a long way from neutral."

A long way? WTF? The market realized that Powell was about to drive the global economy off a cliff Thelma and Louise style and seemed oblivious.

That day marked the top. Within a month, the S&P had shed 20%.

During the decline, Powell hung tough with his hawkish posture. After all, he wasn't going to let the stock market tell him where rates should be.

But then Trump got into the act. Suddenly Powell was on the front page of the newspaper. He was uncomfortable, but still, he didn't alter his stance.

Soon enough though, serious people starting criticizing his intransigence. The ultimate slap in the face occurred with a December 16th, 2018 WSJ Op-Ed by legendary hedge fund manager Stanley Druckenmiller and Kevin Warsh.

Around Oct. 1, global central-bank liquidity reversed and stocks began their descent from peak prices. That is no coincidence. The Federal Reserve should take an important signal from recent developments at its meeting this week.

The Fed created quantitative easing as a novel crisis-response tool a decade ago. It bought assets from the public and stocked them away for safekeeping. Market participants understood the not-so-subtle message: The Fed had investors’ backs. The stock market rallied. The cost of credit fell. And the business and financial cycles charged ahead.

The crisis ended in the U.S. in early 2010, but central-bank asset purchases did not. Other large central banks—the European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan and the Bank of England—followed the Fed’s lead. Together they amassed more than $11 trillion of additional stocks, bonds and other financial assets.

In unheralded news a couple of months ago, quantitative easing gave way to global quantitative tightening as central banks withdrew overall liquidity from the market. True, the Fed had begun to taper its balance-sheet holdings 15 months earlier, but that was more than offset by other central banks’ still-growing asset purchases.

As we head into 2019, quantitative tightening is expected to accelerate. It has been paired with expectations of interest-rate increases from the Fed—and the timing could scarcely be worse.

Economic growth outside the U.S. decelerated over the past three months. Global trade growth also slowed markedly, running about one-third lower than earlier in the year. Growth in some important economies, like China, is significantly weaker. No ocean is large enough to insulate the U.S. economy from slowdowns abroad. And no forecasting model adequately captures the spillovers and spillbacks between the U.S. economy and the rest of the world.

U.S. financial-market indicators also signal caution. Market prices may be showing their true colors for the first time since QE’s expansion. These indicators aren’t foolproof, but they have a better track record than economists. Bank stocks are down about 15% since Oct. 1. Other economically sensitive sectors, like housing, transport and industrials, are down by double digits, underperforming the broader markets. Credit markets are softening, and the decline in major commodity prices is foreboding.

These indicators are at odds with strong U.S. economic growth for 2018, which will come in at around 3.25%. Labor markets also remain strong, although they too are a lagging indicator.

The new Fed leadership team faces the most difficult challenge since Chairman Ben Bernanke and his team confronted shocks to the financial system in 2007-08. They deserve forbearance, not censure. But time is tolling, and the Fed is well-advised to break from the old regime.

The Fed should worry less about fine-tuning its communications strategy and more about getting policy right. In recent months, Chairman Jerome Powell stepped up outreach to Congress and other interested parties. He spoke with refreshing humility about the appropriate policy rate setting. And he prudently scaled back on the kind of pinpoint forecasts his predecessors made. These moves, while welcome, are insufficient.

In response to market tumult, the Fed governors recently hinted at less enthusiasm for rate increases next year. The new forward guidance is different from what they signaled in September. But it is no more reliable. The Fed should stop this option-limiting exercise entirely. And if data dependence is the Fed’s new mantra, it should actually incorporate recent data into its forthcoming policy decision.

The Fed’s balance sheet is where the money is. Yet it has provided little additional clarity on its balance-sheet plans since Chair Janet Yellen’s tenure. At a time of global quantitative tightening and uncertain economic prospects, the Fed’s silence on its asset holdings is contributing to the tumult. We were assured by policy makers that QE provided large benefits to the real economy. If so, won’t its reversal in the form of QT come with a cost? It can’t all be rainbows and unicorns.

In a first-best world, the Fed would have stopped QE in 2010. It might then have mitigated asset-price inflation, a government-debt explosion, a boom in covenant-free corporate debt, and unearned-wealth inequality. It might also have avoided sowing the seeds of future financial distress. Booms and busts take the Fed furthest from its policy objectives of stable prices and maximum sustainable employment.

In a second-best world, on Mr. Powell’s arrival in February 2018, the Fed would have shrunk its balance sheet with speed and determination before raising rates. The economic expansion was still gaining traction at home and abroad. Tax and regulatory reforms were jolting the supply side of the economy from its slumber. Accelerated Fed QT, in the absence of rate rises, would have been much less disruptive to the real economy. Asset prices could then have found a more durable equilibrium and laid a stronger foundation for future growth.

The time to be dovish was when the crisis struck and the economy needed extraordinary monetary accommodation. The time to be more hawkish was earlier in this decade, when the economic cycle had a long runway, the global economy ample momentum, and the future considerably more promise than peril.

This is a time for choosing. We believe the U.S. economy can sustain strong performance next year, but it can ill afford a major policy error, either from the Fed or the rest of the administration. Given recent economic and market developments, the Fed should cease—for now—its double-barreled blitz of higher interest rates and tighter liquidity.

Mr. Druckenmiller is chairman and CEO of Duquesne Family Office LLC. Mr. Warsh, a former member of the Federal Reserve Board, is a distinguished visiting fellow in economics at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution.

Still, Powell didn't budge.

For another eight long days, the FOMC refused to change their stance.

And what happened to the stock market during that period?

The stock market was already down 10% before the op-ed, but then proceeded to lose another 9.5% as everyone waited for Powell to figure out what everyone else already knew - he was too tight!

Eventually, after the pain was too much, Powell tapped out.

And as they say, the rest was history as the stock market took off like a rocket ship (one might even say, the Virgin Galactic type).

Fast forward to today.

Earlier this week I wrote a piece titled "ALL EYES TO THE FED" where I argued the Federal Reserve should get out ahead of this coronavirus crisis. You should have seen my email inbox. It lit up like Snoop Dogg backstage on Martha's cooking show. Some serious credit folk took the time to write me to tell me how wrong I was. They argued the Fed needed to see the data before they would even think of acting.

I guess I should acknowledge that their analysis of the Fed has so far proved spot on correct. The Fed once again seems completely friggin' clueless. FOMC board members have recently indicated they need to see the economic data before they make a decision. Need to see the data? I got a newsflash for them - it's going to be terrible. If they are that stupid that they can't figure out shutting down the second largest economy in the world, then having the virus spread to other countries resulting in more shutdowns will grind the global economy to a halt, then I guess there is no need for me to say anymore.

The entire world knows it's bad. Waiting for some economic number to confirm this reality is the height of stupidity (and we're talking about the Fed here - there are some pretty big historic bonehead moves for competition).

I had thought the human aspect of this crisis would lead the Fed to be proactive. It seemed easier to provide liquidity when the average global citizen needed this from a once-in-a-lifetime-health episode as opposed to Wall Street banks needing it because they used too much leverage in the height of their greed.

Why not get ahead of it because it's the right thing to do for the world economy?

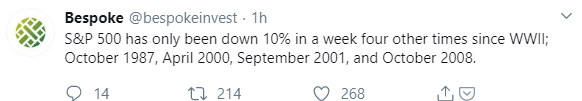

Instead, the Fed has now created a financial crisis. Today's stock market decline puts the current market action in rarefied territory:

In a rather paradoxical development, by waiting so long, if the Fed now eases, it will appear the Federal Reserve is once again saving Wall Street.

Now some people will say, "let it burn. The stock market bulls don't deserve to be saved." Yeah, I get that sentiment. However, the last thing we need is a financial crash on top of a humanitarian crisis.

The time to be tough is not when the world is staring down the barrel of a global pandemic.

And in an interesting development, Kevin Warsh echoed many of my same thoughts in a WSJ Op-Ed today:

A central bank’s primary job is to offset major disturbances to the economy. Today, the novel coronavirus is a material risk to the economy. It represents an unexpected shock, and the Federal Reserve should lead the world’s central banks in taking immediate action.

In a coordinated move alongside the People’s Bank of China, the European Central Bank, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan and others so willing, the Fed should announce a 0.25-percentage-point interest-rate cut and make clear it’s open-minded about further action. The Fed should also encourage other central banks to take appropriate simultaneous action to loosen monetary policy in their jurisdictions. Global action would help make the most of scarce policy ammunition.

Milton Friedman, in his presidential address to the American Economic Association more than 50 years ago, stated that “monetary policy can contribute to offsetting major disturbances in the economic system arising from other sources.” He emphasized that the economic shock must be “major” for monetary policy to be used forcefully and effectively. Friedman was no fine-tuner, but he didn’t believe in passivity during times of trouble either.

More than a decade ago, then-Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke and his colleagues chose to act decisively. When confronted with a major economic shock, the Fed took extraordinary monetary-policy actions, often in coordination with other leading central banks. Acting sooner would have been better, but Mr. Bernanke’s leadership at the Fed was exemplary. Less appreciated but no less important, the Fed benefited from a rich inheritance: a strong, highly credible institution replete with a large reservoir of interest rates to cut and a modest balance sheet with space to grow.

The novel coronavirus presents Beijing with a real test. China’s first-quarter growth is likely to be negative. Aggregate demand is falling fast. Chinese consumers are paring consumption markedly. The inventories of key Chinese exports, including consumer products and intermediate industrial goods, are declining rapidly. High levels of indebtedness, especially at smaller firms, are leading to an increase in insolvencies. Many employees have stayed home in February, which is constraining the production side of China’s economy. It isn’t clear when people will be returning to work or how bad the contagion risks will be when they do.

The window to contain the virus inside China has long since closed. The window to mitigate its effects on the global economy remains open—but not for long. U.S. trade and investment were poised to accelerate this year after a series of new trade accords. But a sudden stop is a clear and present risk to U.S. economic prospects.

Even if the virus is more contained than people think, or dissipates in the spring, economic activity in unlikely to spring back to life. The disruption to global supply chains will take several months to reset. Business confidence in the U.S., which has turned decidedly more negative in recent weeks, will also take to time to reassert itself, especially in an election year. Epidemiologists will ultimately decide whether to categorize the novel coronavirus as a pandemic. Real people, however, won’t wait for the final judgment of experts to make up their own minds.

The signals from financial markets are disturbing. Since the start of the year, commodity prices are off 10%. Oil prices are down nearly 20%. Yields on 10-year Treasury notes—the most important risk-free asset in the world—have tumbled in recent weeks and are now at historic lows.

The U.S. economy is best positioned among the Group of 20 countries, the largest economies in the world, to withstand the shock. U.S. workers’ incomes are growing at the fastest rate in a generation. The unemployment rate is at a 50-year low. Profits for U.S. businesses are near cyclical highs. Productivity has improved markedly in the past year. And the U.S. health-care system is better equipped than any to combat a nationwide outbreak.

If the Fed had normalized policy early in the decadelong recovery, it would be far better situated—in terms of ammunition, efficacy and credibility—to take necessary action now. Still, the Fed has a necessary role to play, even if its tool kit isn’t fully stocked.

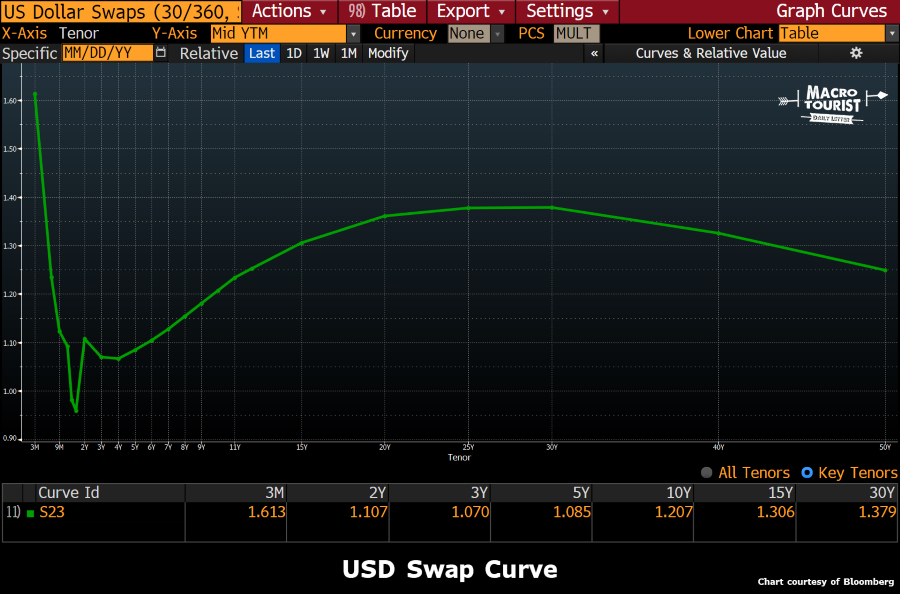

The Fed’s choices in the past 18 months may be contributing to policy inertia. The Federal Open Market Committee chose an awkward time to raise rates in December 2018. The economy was weakening. The FOMC then reversed itself abruptly in 2019, cutting rates cumulatively three-quarters of a point to a current fed-funds rate of about 1.6%. The Fed’s stated rationale for its policy reversal was to ensure inflation moves up from 1.7% to its target rate of 2%.

Fed leaders call the current, ostensibly low level of inflation the greatest challenge for this generation of monetary policy makers. I disagree. An exogenous, uncertain, global economic shock is a far bigger and more pressing challenge. And a far more compelling rationale for policy action.

A coronavirus pandemic would be the biggest threat to the global economy since the financial crisis. We simply don’t know what will happen. The Fed should be in the business of responding to “tail risks”—unlikely events that would have highly damaging effects on output and inflation—not fine-tuning around the base economic outlook.

In 2019, the global economy looked to be trending away from globalization and moving toward regional self-reliance. But the human suffering of the novel coronavirus might not be in vain: Large benefits could result from a timely response to turmoil. This is a time for the world’s central banks to act together in the common interest. For that to happen, the Fed must take the lead.

Mr. Warsh, a former member of the Federal Reserve Board, is a distinguished visiting fellow in economics at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution.

Let's see, last time Warsh wrote a piece, the Federal Reserve ignored him and watched the stock market decline another 10% before finally puking. Will this time be the same? Have they learned so little?

The market has already priced in a ton of easing - why wait until the economic data confirms what every already knows?

These bozos at the Fed are so dumb that as Gordon Gekko once said, "if these guys owned a funeral parlour, no one would die."

The market will now continue punishing the Fed until they give them the liquidity they are demanding.

It's such a shame. They had the chance to do the right thing. To get out ahead of the problem instead of waiting for the market to demand action.

Given Warsh's op-ed, I don't think the Fed can hold off any longer. They waited eight days in December 2018, this time will be less. My bet is that by Sunday night there will be some sort of announcement. At the very least, they will change their tone and start guiding markets towards expecting a cut in March, but I am hopeful they will show some initiative and do more than simply let Wall Street lead them around by the nose.

And one last thought to leave you with. I think if Trump stays in power, Warsh has cemented himself as the next Fed Chairman. And I, for one, wouldn't mind that one bit.

Thanks for reading,

Kevin Muir

the MacroTourist

PS: I am aware that Warsh has sometimes been hawkish as well. I have no problem with that. There is a time and place for both stances. I would take my chances with him deciding on the appropriate policy rather than the current crew any day of the week.